Cecil Griffiths; The Banned Olympian

Cecil Griffiths was the fastest man in Wales and an Olympic gold medallist who, after falling foul of the IAAF, was cruelly denied his chance at sporting. immortality.

Wales is a small but proud nation. One area in which it has long punched above its weight is on the sports field. The nation has produced world class boxers, rugby players, footballers, cyclists and swimmers.

Despite producing a string of world class athletes, only 4 Welshmen have ever won athletics gold at the Olympic games: David Jacobs, John Ainsworth-Davis, Cecil Griffiths and Lynn Davies. Of these 4 men, it is the story of Cecil Griffiths that interests us today.

To Begin at the Beginning

Cecil Redvers Griffiths was born on the 18th of February 1900. His father, Benjamin Griffiths was a former able-bodied seaman who, after leaving the Royal Navy, settled in Neath.

A respected local businessman, Benjamin Griffiths served as a town councillor and a committee member of Neath RFC. In 1892 he married Sarah Trick, together the couple had a number of children. Sadly only Cecil and his older siblings Ben and Eva survived past infancy. The family suffered further tragedy when, in 1908, Benjamin died.

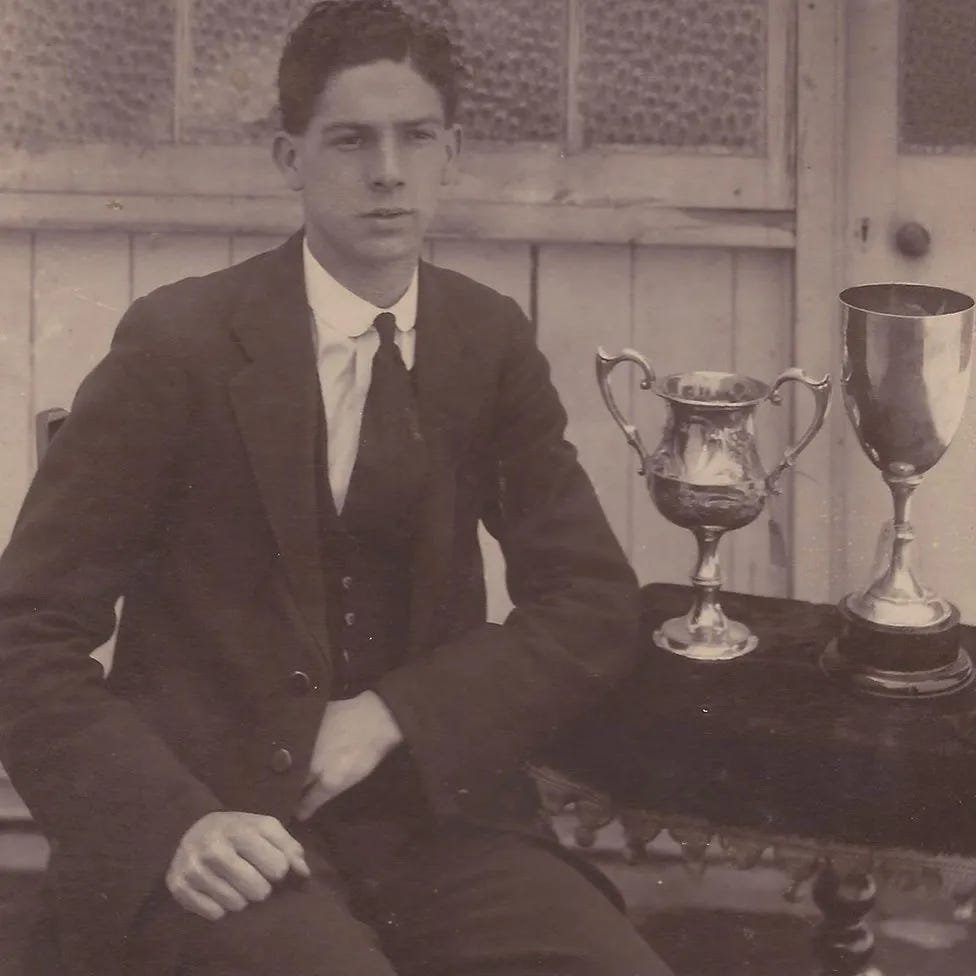

Young Cecil was a keen sportsman, regularly competing in running races organised as part of local fairs and social events. He also played on the wing for Neath RFC’s junior teams.

During World War One, organised sport was initially put on hold. However, as time went on, fundraising events, intended to raise morale and money for the war effort, began to take place. Often these events were advertised in local newspapers with the promise of small, financial prizes to the winners.

Griffiths competed in a number of these events including one on the Cwrt Herbert fields. Organised as part of the 1915 Great September Neath Fair, Griffiths won the race and a small cash prize.

It was at this fair that he met his future wife, Gladys “May” Rees. Marrying in St David’s Parish Church in July 1922 the couple had two sons, John and Cecil.

Griffiths won another small financial prize at a race in Neath Abbey in 1917. The race was part of an event organised by his uncle, William Trick, the twice mayor of Neath.

After leaving school, Griffiths went to work at the Great Western Railway depot in Neath. Following his 18th birthday Cecil Griffiths volunteered for the Queen’s Westminster Rifles, a Territorial Army Regiment based in London. Cecil’s father was originally from London and his paternal uncle had links to the regiment.

While the War ended before Cecil Griffiths could see active service, his time in the army did help to kick start his running career. At the 1918 Inter-Services Championship at Stamford Bridge, Griffiths represented the army in a number of races, including the 440 yards.

Griffiths’ performances at the Inter-Service meets brought him to the attention of Surrey Athletic Club. Following the end of the war, the club approached Griffiths with the offer of a job in their owner’s factory and a home if he agreed to represent them at athletics meetings. Griffiths agreed and was soon settled into a home in the London suburbs.

In 1919 Griffiths made his debut at the AAA Championships, running for Surrey. He finished 3rd in the 440 yard race. A repeat of this result the following year earned Griffiths a place in the Great Britain team for the 1920 Olympics.

Whilst Griffiths was making a mark on the track the Amateur Athletic Association, athletics governing body in the UK at the time, were debating what to do about the significant number of athletes who had competed for prize money during World War One.

At the time, athletics maintained a strict amateur policy. Anyone who won a financial prize was classed as a professional and banned from competing in amateur competitions. But the war years had been a time of hardship and uncertainty for many. Banning athletes based on their actions during this period seemed harsh.

It was also impractical. Poor record keeping during the period, coupled with the fact that many events were orgnised locally and without the knowledge of the AAA meant that it would be impossible to trace everyone who had competed in a race during the period.

Eventually the AAA reached a decision. At their AGM in 1919 a resolution was passed allowing athletes who, under “special circumstances”, had earned money during the war years to rejoin the amateur ranks and compete in international competitions.

What exactly those “special circumstances” were remains unclear. But it seemed that Griffiths was now free to run for both his club and country.

The 1920 Olympics

Held in Antwerp, Griffiths was slated to compete in both the individual 400m and 4x400m relay. While illness caused him to miss the individual event, Griffiths was well enough to compete in the relay.

Griffiths ran the first leg in a time of 50.6 seconds before passing the baton to Robert Lindsay. Together with John Ainsworth-Davis and Guy Butler the team completed the race in a time of 3:22.2, taking gold ahead of South Africa and France.

Griffiths was just 20 at the time of the race; one of the youngest British athletes to ever win a gold medal.

Griffith’s place in the individual event was filled by his relay teammate, Aberystwyth born John Ainsworth-Davis.

Ainsworth-Davis finished 5th behind winner Bevil Rudd. The South African clocked a winning time of 49.6. Silver went to Guy Butler of Great Britain in a time of 50.1 and bronze to Sweden’s Nils Engdahl in 50.2.

It is not fanciful to imagine that Griffiths could have won a medal of some colour in the race had he been fit. At the following year's Welsh Championships he recorded a time of 49.8 seconds over 440 yards.

Unlike today, where Olympic athletes are heralded as sporting heroes, Griffiths returned home following the conclusion of his event and was back at work the following day.

In September 1920 Griffiths was part of the British Empire team that broke the British record for 4x440 yards in a time of 3:20.8.

The Fastest Man in Wales

Cecil Griffiths was a remarkable athlete with an easy running style.

In 1921 he again came third at the AAA championships and, at the Welsh Championships, recorded the Welsh record for the 440 yard race with a time of 49.8 seconds. Set on a bumpy grass track at Barry Island Griffiths’ record would stand for 32 years. For context this time, when converted to 400 m, would have been good enough to win the title at the Welsh Championships in 2012. Griffiths also set the Welsh record for the 220 yards at the same meeting.

In 1921, despite being Welsh, Cecil Griffiths was selected in the England team for an international athletics meeting against France in Paris. At the time Wales was considered part of the English counties system. It wasn’t until 1934 that a Welsh team would compete at the Empire Games and a further 14 years before the Welsh AAA was formed.

Additionally, Griffiths had lived in England since he was 18 years old, he almost certainly qualified on residency grounds or via his English born father.

At the meeting Griffiths came second in the 400m race and was part of the winning relay team. In the return fixture at Stamford Bridge the following year Griffiths won the 400m in a time of 50.8 seconds and came second, behind Edgar Mountain, in the 800m.

In 1922, with the Welsh Championships now being held at Cardiff Arms Park, Cecil Griffiths moved up a distance to 880 yards. Again he broke the Welsh record. Over the same distance in the AAA championships he came second.

Arguably Wales’ finest runner, between 1920 and 1924, Griffiths claimed 10 Welsh titles including 5 successive 440 yards titles. In 1922, 1923 and 1927 he also won the 880 yard title.

In both 1923 and 1925, Griffiths won the 880 yards at the AAA Championships. Over the same distance he placed second in 1927 and third in 1924 and 1926.

Chariots of Fire

Following another successful season in 1923, Griffiths’ thoughts turned to the 1924 Olympics.

However, bad news was to come in the shape of the International Amateur Athletics Federation, the sports global governing body. They, along with the AAA announced that Griffiths was banned from competing because he had received prize money for winning races. The charges dated back to 1917 when the young Griffiths competed in unregistered races in the Neath and Swansea area.

Questions persist to this day over why Griffiths was banned when he was.

That he was permitted to compete in the years from 1917 to 1923, including at the 1920 Olympics, suggests that the authorities either didn’t care about his past or were ignorant of it. If the latter was the case, where had the new information come from? Certainly not from Griffiths himself.

Besides, the AAA had previously agreed to an amnesty over runners who had competed for money during World War One. Surely that applied to Griffiths?

The unfortunate athlete hadn’t even won a fortune. The prizes amounted to less than £10 in total. And, at the time, Griffiths had no ambition of becoming an athlete.

Some people have suggested that, at a time when class and family background still held sway, the authorities sought out a reason to exclude Griffiths because he was a working class boy and didn’t have a privileged background or an Oxbridge education.

Whatever the reason, the decision certainly smacks of double standards. Griffiths wasn’t the only athlete to have won prize money during the First World War period; if the practice hadn’t been so widespread then the AAA wouldn’t have issued an amnesty in 1919. Additionally, other athletes, such as Harold Abrahams, were allowed to employ a professional coach during the games. Something that was also against the rules of amateurism.

Griffiths was eventually reinstated as a professional athlete and allowed to compete in domestic competitions. However, he was still banned from representing Great Britain in international competitions meaning that he was to miss the 1924 Summer Olympics.

The 1924 Summer Olympics were famously depicted in the film Chariots of Fire.

As anyone who has seen the film knows, Eric Liddell learns on the boat to France that the heats for the 100m are scheduled to run on a Sunday. A devout Christian, Liddell is unable to compete on the Sabbath so switches to the 400m.

In reality, Liddell knew the date of the heats several months before the start of the Olympics. He had already made the decision to move up in distance and had been specifically training for the 400m.

While Griffiths had moved up a distance to the 800m or 880 yards, he was still one of the finest 400m runners in the country. If Griffiths had been eligible for selection it is debatable whether Liddell would have made the team. Griffiths was the faster man over the distance and Liddell had, at the time of selection, not achieved the specific standard.

In the end, Griffiths didn’t fight the ban. In fact, when Liddell won the 400m, he expressed his delight for his friend. But it did cause him much mental anguish.

Rubbing further salt into the wound, at the Kinnaird Trophy meeting held a month before the games, Griffiths defeated Douglas Lowe, the man who would win the 800 m in Paris.

Continued Success

At a meeting in Fallowfield Stadium in Manchester in 1924 Griffiths set a time of 1:54.6 in the 880 yards handicap off scratch. This equalled the time set by Francis Cross in 1888 and Henry Stallard a few weeks earlier at the AAA Championship. However it was never ratified as a British record.

During the course of his athletics career Griffiths set 3 of the best times recorded by a British runner in the 880 yards and 1,000 metres.

A remarkable feature of Griffith’s success was his consistency. He was a finalist at the AAA Championships in either the 440 or 880 yards for 9 successive years.

Despite all the medals and trophies, one of Griffith’s finest races saw him place 3rd.

The 1926 AAA Championship at Stamford Bridge drew a crowd of 35,000 keen to see how Douglas Lowe, Britain’s double Olympic champion, would fare against the German track star Otto Peltzer over 880 yards.

Following World War One, Germany had been banned from many international sporting events, including the 1920 and 1924 Olympics. The invitation for a group of athletes to compete in the AAA Championship marked the start of Germany’s return to international competition.

Griffith’s, as the defending champion over the distance, was expected by many to give the two men a good race. Lining up alongside Griffiths, Lowe and Peltzer was the hurdler Wilfred Tatham.

With Tatham acting as pacemaker, the runners set off at a lightning quick pace. By the time they reached the end of the first lap, Lowe had decided that Tatham wasn’t running quickly enough and had overtaken him.

To the delight of the crowd, and with Peltzer and Griffiths in close pursuit, Lowe completed the first lap in 54.6. This was well under World Record speed.

It wasn’t until the final yards that Peltzer finally passed Lowe, winning the race in a UK all-comers record time of 1:51.5. Lowe placed second in an estimated time of 1:52.0 while Griffiths came third.

We don’t know Lowe or Griffith’s exact times because, according to The Times, the “timekeepers were too overwhelmed by the occasion” to record them. Griffith’s finishing time is estimated to be around 1:53.1. Not only was this a personal best for the Welshman but no other Welsh athlete would match this time until Reg Thomas and Jim Alford in the 1930s.

The Final Race

At the 1928 AAA Championships Griffiths suffered a bad injury when another runners spikes cut his leg open. Bleeding heavily, Griffiths was carried from the track. It was a sad end to a stellar career.

Cecil Griffiths retired from athletics in 1929.

Like many, Griffiths would lose his job in the Great Depression. To make ends meet he sold most of the trophies and medals that he had won over the previous decade. The only medal that he kept was the gold he won at the 1920 Olympics.

Eventually Griffiths found employment at the coal depot office of the London Co-Operative Society in Edgware.

At the start of World War Two, Griffiths joined his local home guard regiment. Here, his quick thinking saved the life of a fellow soldier who had dropped a live grenade by throwing it over a blast wall before it could explode.

Tragically Cecil Redvers Griffiths was just 45 years old when he died of heart failure after collapsing on the platform of Edgware Road Station. He was buried in an unmarked grave at St Lawrence’s Church in Edgware.

Cecil Redvers Griffiths was one of Wales’ greatest athletes. In addition to his many trophies, medals and records he was the first person to be posthumously inducted into the Welsh Athletics Hall of Fame. He has also been inducted into the Welsh Sporting Hall of Fame.

Following campaigns by his family he was recognised by a blue plaque at Cwrt Herbert Sports Centre, the venue of his first friendly race, and Cecil Griffiths Close in Tonna.

In May 2022 a memorial stone made from Welsh slate was unveiled at his grave.