The Forgotten Tradition of Sin-Eating in Wales and the Marches

Today, the sin-eater is a piece of folklore rooted firmly in the Appalachian traditions so it may surprise you to learn that for centuries sin-eaters operated throughout Wales and the Marches.

Up until the mid 19th century the sin-eater played an important role in the post-death rituals of many communities across Wales and the Marches, the border counties between Wales and England. Today their existence is barely known.

Join me as I explore the role of the sin-eater in society, the reasons for their rise to prominence and why, today, they are largely forgotten.

What is a Sin-Eater in the Welsh Tradition?

In a period of high religious observance, sin-eaters were often feared by people who worried that their work was some form of dark magic or witchcraft. More superstitious people would even avoid looking the sin-eater in the eye for fear of bringing bad luck on themselves or their family. Consequently, they often lived away from the village, often as an outcast.

In 1926 Bertram S. Puckle published an account of a sin-eater given by Professor Evans of the Presbyterian College in Carmarthenshire. Professor Evans had encountered a sin-eater near Llanwenog, Cardiganshire during the mid 1820s.

Evans described how the sin eater was “abhorred by the superstitious villagers as a thing unclean” who had “cut himself off from all social intercourse with his fellow creatures by reason of the life he had chosen; he lived as a rule in a remote place by himself and those who chanced to meet him avoided him as they would a leper.”

Professor Evans also noted that the sin-eater was “held to be the associate of evil spirits, and given to witchcraft, incantations and unholy practices; only when a death took place did they seek him out, and when his purpose was accomplished they burned the wooden bowl and platter from which he had eaten the food handed across, or placed on the corpse for his consumption.”

What Did a Sin-Eater Do?

Following a death, family or friends would make a cake. After baking, the cake would be placed on the corpse. People believed that as the cake cooled, it absorbed the sins of the deceased.

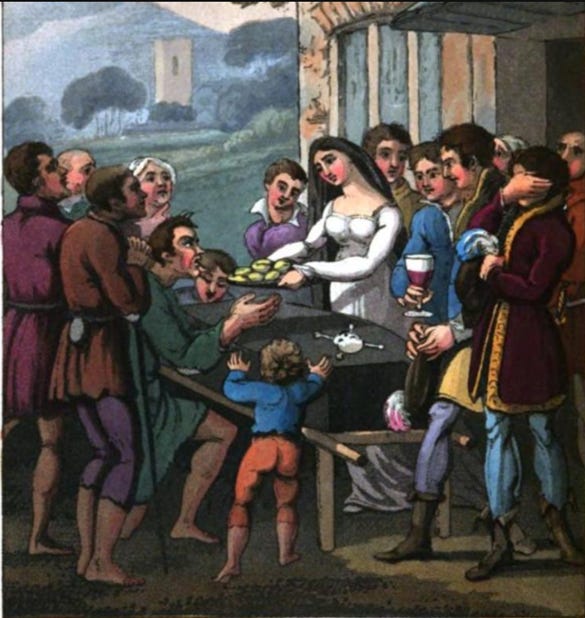

Once the cake had cooled, the sin-eater would be invited into the home and seated beside the deceased. The cake and a drink of ale would be passed over the body to the sin-eater. By eating the cake, the sin-eater took on the sins of the deceased allowing them to enter the kingdom of heaven.

After accepting payment, the sin-eater left the home, often amid the curses of the mourners.

While the main element of an item of hot food being placed on the deceased to cool and absorb their sins remained the same, sin-eating ceremonies differed slightly from area to area.

In Llanllyfni there was a Coeden Bechod or Tree of Sin. Following a death, the family would place a hot potato or cake on the chest of the corpse where it would cool, absorbing the sins of the departed. The food, along with a few coins as payment, was then placed beneath the Coeden Bechod where it was eaten by the sin-eater.

During the 1920’s, Charles Owen of Snowdonia recalled that the custom was for family and neighbours of the deceased to contribute towards the making of a cake using the best ingredients available. This was important because the better the cake the more likely the sin-eater was to eat all of it. If part of the cake was left it meant that the deceased’s sins had not been completely forgiven, condemning them to purgatory.

In parts of North Wales, a bowl of milk instead of a bowl of ale was given to the sin-eater. In other areas a baked potato still in its skin was offered, underlying the importance of the wholeness of the offering.

John Aubrey, a 17th century diarist, is our earliest source on this custom. At the time Aubrey recorded sin-eating taking place in Herefordshire, it was already starting to fade from common usage.

In ‘The Remaines of Gentilisme and Judaisme 1686 - 1687’, Aubrey described the practice of hiring poor people to attend funerals to take upon the sins of the deceased. Aubrey described how a sin-eater who lived in a cottage on the road to Ross carried out his duties: “The manner was that when the corpse was brought out of the house and laid in the Biere; a Loaf of bread was brought out, and delivered to the Sine-eater over the corpse” the sin-eater was also given “sixpence in money, in consideration whereof he took upon him all the Sinnes of the Defunct”.

Folklorist E. Sidney Hartland recorded an account of sin-eating that was given to an 1852 meeting of the Cambrian Archaeological Association by Matthew Moggridge. An antiquary from Swansea, Moggridge spoke of the custom surviving “to within a recent period”.

In Llandybie, Moggridge told the audience, it was customary, following a death, for the deceased’s friends to send “for a Sin-eater of the district, who on his arrival placed a plate of salt on the breast of the defunct, and upon the salt a piece of bread. He then muttered an incantation over the bread, which he finally ate, thereby eating up all the sins of the deceased. This done, he received his fee of 2s. 6d. and vanished as quickly as possible from the general gaze; for, as it was believed that he really appropriated for his own use and behoof the sins of all those over whom he performed the above ceremony, he was utterly detested in the neighbourhood – regarded as a mere Pariah – as one irredeemably lost.”

Hartland established that while sin-eating had died out during 19th century it had been “formerly observed in Wales and the Welsh Marches”

The Evolution of a Ritual

In some parts of the Marches the practice evolved away from an individual sin-eater. Instead, family, friends and neighbours would come together to eat and drink around the deceased and would, in doing so, absolve them of their sins.

Ella May Leather collected folk stories from around Herefordshire in the early 20th century. She detailed the experience of one man who attended a farmhouse wake. Upon declining a glass of port the man was told by the old farmer “but you must drink sir. It is like the Sacrament, It is to kill the sins of my sister.”

Similarly, an 1893 service at a house in Market Drayton, Shropshire saw a lady pour out a glass of wine for each of the bearers. This, along with the funeral biscuits, was then passed over the coffin for the men to consume.

The consumption of funeral biscuits, typically two sugared biscuits wrapped in wax, and burial cakes was common throughout rural England. In parts of Cumberland and Lincolnshire, burial cakes are still made today.

During the first half of the 20th century, in some parts of Wales the custom was to send a bag of funeral biscuits or arvel bread with the deceased’s card. In other areas the arvel bread was passed around the funeral party; after taking a piece the mourner placed a shilling on the plate.

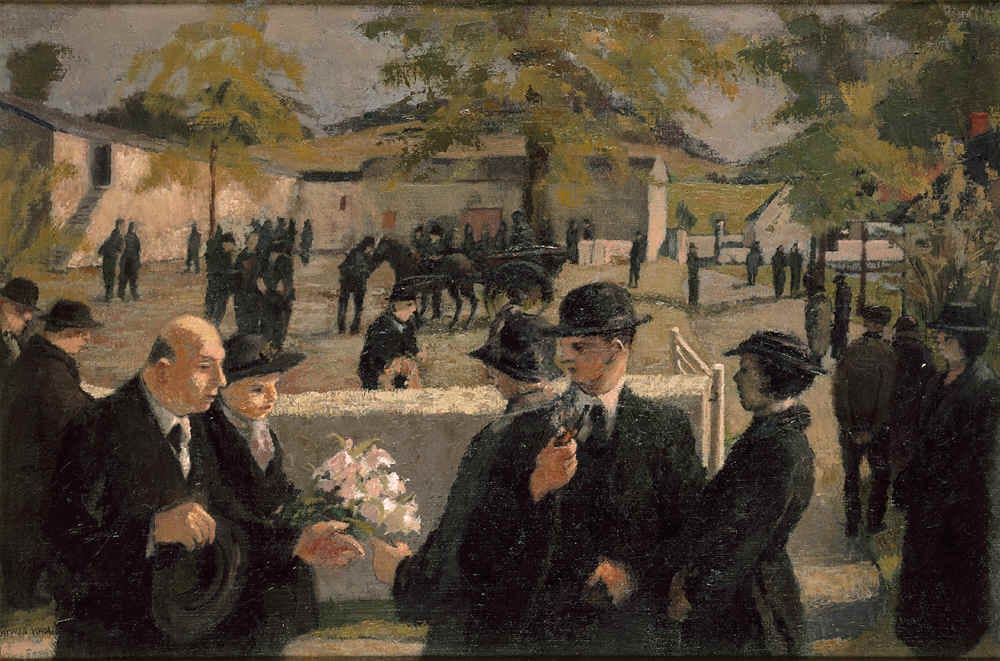

In the north of England arvel bread would be given to mourners to take home or distributed to the poor.

The practice could also be found in Europe.

In the Netherlands, people made dead cakes or doed koecks, marked with the initials of the deceased; a practice that was taken by immigrants to old New York. Similarly, on the Balkan peninsula small bread in the image of the deceased was made and eaten by the surviving members of the family.

In parts of Germany it was customary to bake a corpse cake. After being placed to cool on the deceased, the cake was eaten by the nearest relative.

Elsewhere, the ritual evolved so that the minister who performed the service took on the sin. When White Kennet (1660-1728) Bishop of Peterborough and antiquary came into possession of some of Aubrey’s manuscripts he added a reference to “Amersden in the county of Oxford”. Here Kennet recorded “at the burial of every corps one Cake and one flagon of Ale just after the interment was brought to the minister in the Ch[urch] porch”.

The Last Sin-Eater

Richard Munslow, a resident of Ratlinghope, Shropshire is said to be the last sin-eater.

Interestingly, Munslow, who died in 1906, didn’t match the usual profile of a sin-eater. Unlike many who took on the role, he was not an societal outcast but a well-respected farmer. This has led to speculation that Munslow revived the practice following the deaths of his first three children. Initially providing a way for him to cope with his own grief, Munslow may have continued the practice to give reassurance and comfort to other bereaved families.

Munslow’s story provided some of the inspiration for Mary Webb’s 1924 novel Precious Bane.

In 2010 local people collected money to restore Munslow’s grave, highlighting the custom and his unique place in history. The then vicar of the parish, Norman Morris commented that “it was a very odd practice and would not have been approved of by the church but I suspect the vicar often turned a blind eye to the practice.”

Why are Sin-Eaters Forgotten?

The sin-eaters’ fall from public consciousness is not so unusual when you consider the seismic change that the Industrial Revolution caused in Welsh society.

Huge numbers of people left their small, rural communities to live in larger towns and villages. Consequently, many folk traditions and rituals were either amended or abandoned.

There was also the Blue Books.

Correctly known as ‘The Reports of the Commissioners of Inquiry into the State of Education in Wales’ this was a three-part publication commissioned by the government in 1847. The report was scathing, criticising non-conformity, the Welsh language and the morality of the Welsh people.

In the aftermath of the Blue Books, Wales and her people were subject to endless campaigns promoting sobriety, morality and education. For many leading members of Welsh society it wasn’t enough to discourage and deny the “old beliefs”, a modern, Christian Wales had to be created in its stead. Talk and practice of the old ways was widely discouraged.

In this devout environment, many denied the existence of folk-traditions such as sin-eating. Consequently, most of the accounts we have detailing the practice are second or third hand accounts recorded long after the fact, by folklorists and antiquaries.

With little written evidence of sin-eating, many historians dismissed the existence of the ritual in Wales and the marches. Some have even gone so far as to claim that John Aubrey, the first person to record sin-eating in Wales and the Marches had fictionalised the account.

The Truth Behind The Myth

The sin-eating ritual, eating bread and drinking wine or ale over the corpse, shares similarities with the Christian Eucharist. While some have theorised that sin-eating is pre-Christian, this Eucharist-like element suggests that the ritual is underpinned by Christianity.

It is possible that sin-eating was a remnant of post-reformation attempts to preserve elements of the Catholic funeral practice. For many conservative communities, the Reformation of the 1540s was a deeply traumatic event. Many rituals of faith were banned or erased; this included aspects of the funeral service. The ringing of bells, reciting of funeral masses and the distribution of funeral doles all ceased.

Funeral doles, a common part of Catholic wills, were charitable handouts. Distributed at funerals to the poor of the parish they usually consisted of provisions of bread and ale. The doles formed part of an unwritten contract; in return the recipients would pray for the soul of the deceased.

The specification that the doles were to go to the poorest related to the idea that the poor were closer to God than the rich. Therefore their prayers were worth more, reducing the amount of time the deceased spent in purgatory before entering heaven.

Following the reformation, the church attempted to suppress the concept of purgatory, arguing that it had no basis in the Bible. This would have caused significant distress in communities where elements of the old faith persevered. There is evidence that Catholicism persisted in rural Wales until the 16th century and funeral doles were common until the 19th century.

Certainly, the emergence of sin-eaters in Wales does seem to coincide with the demise of Catholicism and the banning of funeral doles. Aubrey noted that the ritual was “rarely used in our dayes” but had been observed in a number of places even at the height of the Cromwellian government of the 1650s when religious restrictions were strictly enforced.

At a time of high faith and religious observation, sin-eaters played an important role in society. In her essay ‘The Gift of Suffering’, Ingrid Harris suggests that the practice of sin-eating may have been an attempt to regain the lost sacraments from its Catholic roots.

By the 18th century the Eucharist was firmly ingrained in popular consciousness as was the concept of bread symbolising the soul. Antiquarian Henry Curzon wrote in 1712 about villages in Herefordshire hiring poor people to “take on them the Sins of the Deceased” and also piling “high heaps” of cakes on tables to honour the dead on All Souls Day.

In some areas, the link went further; in the hours following a death families would summon the sin-eater over their local Anglican priest and the sin-eater would even listen to confessions from the bereaved family.

Eventually, as society changed and the newer forms of worship became more ingrained in society the role of the sin-eater began to fade from prominence replaced, in the hours and days after death, by priests and ministers.

Thank you for this piece. It is very helpful for my current research into historical Welsh traditions and rituals around death.