The Impossible Viaduct

The story of the tallest railway viaduct in the UK and a marvel of the Victorian age.

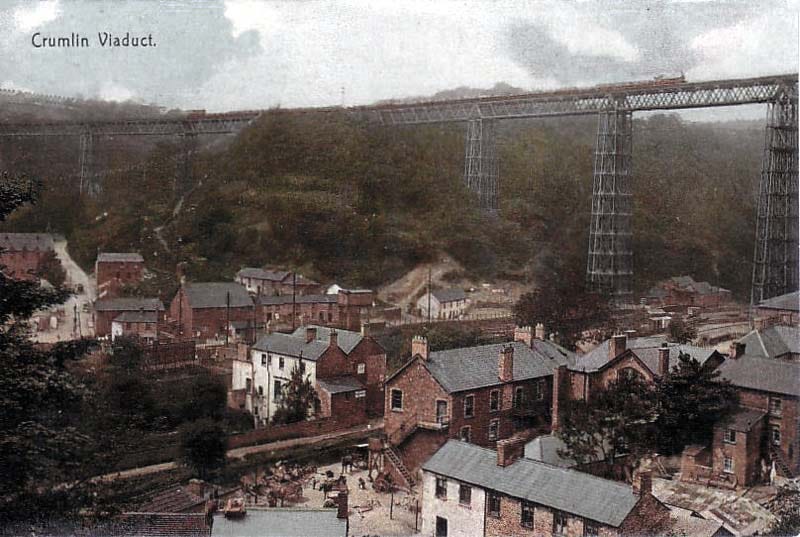

The Crumlin Viaduct was one of the wonders of the Victorian age. The highest railway viaduct ever constructed in the UK, it was also the third-highest viaduct in the world.

Over 200 ft tall and 1,638 ft long this impossible-looking bridge spanned both the Ebbw and smaller Kennard Valley, carrying steam trains along the skyline. But why was it constructed and what became of it? This is the story of the Crumlin Viaduct.

The need to construct the Crumlin Viaduct was driven by the 19th century ‘South Wales coal rush’. Initially, railways were constructed from north to south, enabling coal to be taken from the valley mines to the ports in Newport, Cardiff and Barry. From here, the “black gold” could be shipped around the world.

By the early 1850s, it was clear that more rail infrastructure was needed. A line running east to west, joining the Taff Vale Railway in the west with the Newport, Abergavenny and Hereford Railway in the east was proposed. Known as the Taff Vale Extension, those building the new line had a major problem to solve; how to cross the Ebbw Valley.

Charles Liddell, the chief engineer of the Newport, Abergavenny and Hereford Railway (N.A.H.R), dismissed the construction of a stone bridge. The valley was steep-sided and frequently buffeted by ferocious winds. A stone viaduct would not only be difficult to construct, it would also be expensive. Instead, other solutions were explored.

Thomas William Kennard, a railway engineer, proposed a viaduct of 10 iron trusses supported by high stone piers. This was accepted by Liddell and the N.A.H.R. and work began in the summer of 1853. While deep foundations were constructed in the valley floor, the iron for the span was made at the nearby Blaenavon Iron and Coal Company works. This was owned by Kennard’s family as was the Falkirk Iron Company which produced the castings for the bridge.

During the construction process, Thomas Kennard built a house nearby. Named Crumlin Hall, it enabled Kennard to keep a close eye on his project.

It is not surprising that Kennard wanted to keep a close eye on the works. Constructing the bridge was both difficult and dangerous. Despite this, there was only one fatality, which happened when a girder slipped whilst being hoisted into position.

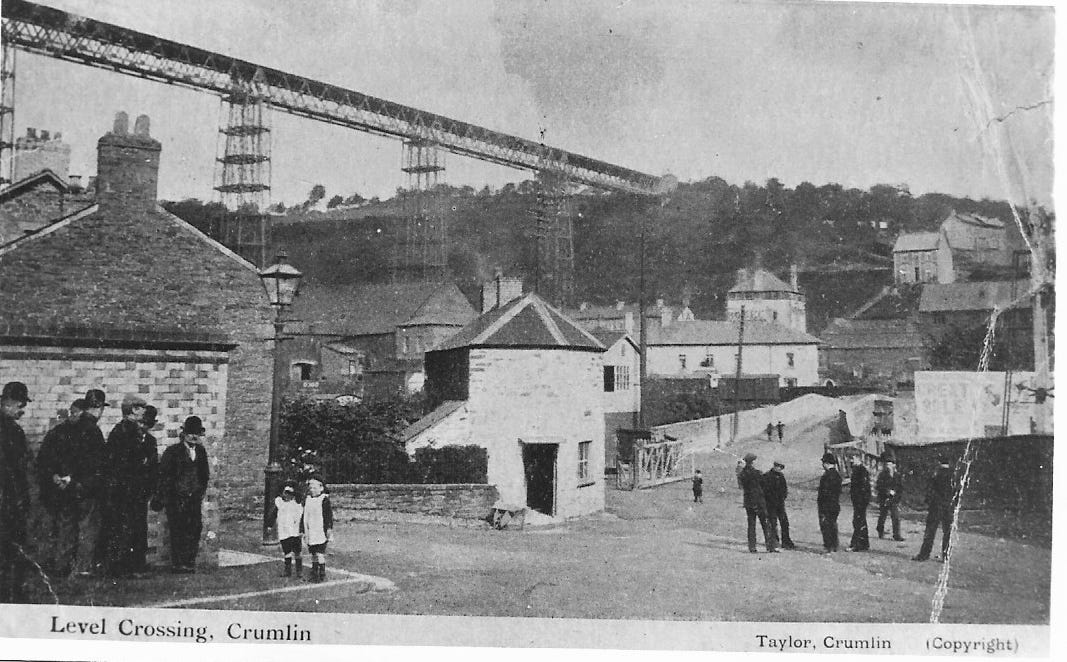

Even during its construction, the bridge drew crowds of curious onlookers. Local newspapers also regularly reported on its progress.

On the 9th of May, 1857 the Illustrated Usk Observer and Raglan Herald reported that testing was being carried out on the bridge, prior to an official government inspector arriving. The approval of the inspector was needed before the line could be opened to traffic. The report also claimed that during testing, the experienced engine driver Charles Langham of Panteg had already driven the first passenger train over the viaduct.

On the 23rd of May, 1857 Colonel Wynne, the government inspector, visited Crumlin for final testing. After inspecting the bridge he watched as 6 locomotives towing tenders weighing 50 tonnes and trucks laden with coal and metal ran back and forth over both lines. Following the test, Wynne was satisfied and the Crumlin Viaduct was given official permission to open.

Initially, Crumlin Viaduct was painted white. This was later changed to a dull, dark rusty shade of red.

The final cost of constructing the Crumlin Viaduct was £62,000. Significantly cheaper than a stone bridge.

To widespread interest, Crumlin Viaduct was officially opened in a grand ceremony on the 1st of June 1857. Canons positioned on the surrounding hillsides set off celebratory shots which echoed throughout the valley.

Over 20,000 people came to watch as Lady Isabella Fitzmaurice declared the bridge open. The first train then crossed the span and entered the Bryn tunnel. Here its journey ended; the Hengoed viaduct on the other side of the tunnel, another of Kennard’s projects, was not yet complete and ready to carry rail traffic.

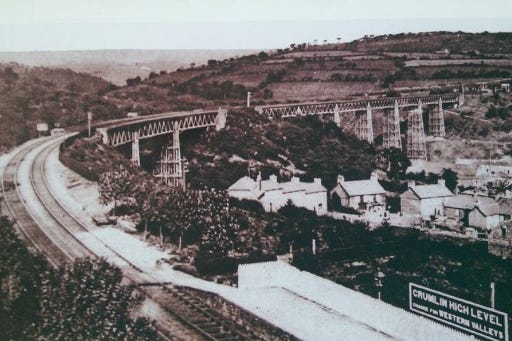

On the west side of the viaduct, Crumlin High Level station was constructed to serve passengers. Opening on the 8th of October 1857 it initially proved popular with people wishing to see and cross the famous bridge.

In addition to local passenger services, the newly opened line provided a direct route to the East Midlands. This was used to speed up the transportation of coal from the South Wales coal fields.

As the Chief Engineer of the N.A.H.R, Charles Liddell had predicted, the location of the Crumlin Viaduct soon proved to be problematic. The high winds that rattled through the valley meant that the structure was prone to swaying. On one occasion this was found to have loosened some of the girders on the bridge.

In 1898 a tragic accident was avoided when a wagon lost its wheel and derailed whilst crossing the bridge. Luckily the accident happened at night when the line was quiet and not during the day when passenger services regularly crossed.

In 1902, subsidence, caused by mining work in the valley below, started to undermine the foundations of the bridge.

A tragedy occurred on the 28th of October 1914. A group of men were using a staging of timber planks to paint the bridge. When one of the supports broke the foreman, Mr Skevington, fell 175 ft to his death in the goods yard below. A second man, Thomas Bond, was able to grab one of the bridge’s girders as he fell.

With Bond dangling in midair, Bridgeman James Dally, who was supervising the works, cautiously crawled from the gangway onto the narrow diagonal bracings. Risking his own life he managed to pull Bond to safety. Mr Dally was rewarded with the Edward Medal for his heroism.

World War Two saw conflict brought to the home front. As well as the threat of invasion and aerial bombing campaigns, there was a real fear that important pieces of national infrastructure, such as railways, may fall victim to enemy saboteurs.

On the 21st of August, 1941 a suspected spy was arrested by the National Reserve who were guarding the bridge. The man was taken for questioning by the army before eventually being released. He was merely an amateur photographer who was visiting the area and had decided to take a few snapshots of the famous Crumlin Viaduct.

The need to carry out regular maintenance work on the Viaduct as well as the height and steepness of the line meant that the Newport, Abergavenny and Hereford Railway was one of the most expensive lines to operate in the UK. Unsurprisingly, following nationalisation in 1947 British Rail attempted to cut costs by reducing the line to a single track.

During the 1950s passenger numbers started to decline. By the end of the decade, the line was barely used. Like many other once-popular branch lines it was earmarked for closure.

On Saturday the 13th of June 1964 the 20:55 passenger service from Pontypool Road to Aberdare High Level, crossed the Crumlin Viaduct before stopping at Crumlin High Level station It was the last train to cross the Crumlin Viaduct. (A later, eastbound train from Neath General to Pontypool Road was scheduled to cross the bridge, but the train terminated at Aberdare.)

Crumlin High Level station closed to passengers on the 15th of June, 1964.

After its closure, there were hopes that the Crumlin Viaduct could be preserved in some form. It was scheduled as being of architectural and historical interest. However, structural surveys showed it to be in a poor state of disrepair. Simply making the structure safe was an expensive task. When the predicted cost of ongoing maintenance was added to this, it was decided that preservation was too expensive to persue.

Demolition of the Crumlin Viaduct began in June 1965. The work was carried out by Birds of Swansea.

In 1966, a film crew from Universal Pictures arrived to shoot scenes for the movie Arabesque on the Viaduct. For the final time, Crumlin Viaduct found itself the centre of attention as crowds flocked to see the movie's two stars, Gregory Peck and Sophia Loren in action.

By the end of 1967, all that remained of the tallest viaduct in the UK were the stone abutments on each side of the valley.