The Tragic Tale of Tommy Jones

At the foot of Pen Y Fan, between Pen Milan and Corn Ddu stands an obelisk, marking the spot where the body of little Tommy Jones was discovered. This is his story.

The Maerdy of 1900 was a close-knit, vibrant coal mining community. Among the many young families that had chosen to make the village their home were the Jones family; William, his wife Ann Lucretia and their children Elizabeth Jane and Thomas Williams.

While Lucretia (she favoured her middle name over her Christian name, was born in Cwmbach, she had grown up on Maerdy Road in the growing town. In contrast, William had, like many men, arrived in the Rhondda in search of employment.

William, one of seven children born to William and Janet Jones, grew up on a hill farm in the Bannau Brycheiniog (Brecon Beacons) where his father worked as a shepherd. After leaving school, the young William started work as a farm labourer for the Evans family of Troedyrhiw farm.

Troedyrhiw farm sat on the divide between the Rhondda Fach and Rhondda Fawr valleys. From there William was perfectly placed to observe the transformation of the Rhondda as coal mines sprung up across the valley floor.

Soon after the 1891 census was taken the 22 year old William left Troedyrhiw farm for the last time to start a new life as a coal miner. While his new line of employment was far more dangerous it was also better paid.

In 1893 William married 18 year old Ann Lucretia Davies. They settled at 9 James Street and soon welcomed two children; Elizabeth Jane and Thomas Williams.

A Bank Holiday Trip

As spring turned to summer, William decided to use the extended break afforded to him by the August bank holiday weekend to take 5 year old Tommy on a trip to visit his grandfather.

By 1905, William senior had taken on the running of Cwm Llwch, a small farm that sat on the slopes of Pen Milan near Libanus. The elderly widow lived there with his daughter Jennet Jones, 4 year old niece also called Jennet Jones and his 13 year old nephew William John Jones.

After a wet week, Saturday the 4th of August began fine and dry. A gentle breeze helped to keep the early summer temperature on the cool side. Holding his fathers hand tightly, little Tommy, smartly dressed in a sailors suit, excitedly walked to Maerdy train station. There they would catch the train to Pontypridd.

At the bustling Pontypridd station, the pair crossed the platform and boarded the Merthyr Tydfil train. There they would change trains for a second time, this time boarding one heading to Brecon. As the train left Merthyr, little Tommy watched through the carriage window as the scenery transformed from dark, industrialised valleys into lush, green hills.

After climbing steeply, the train entered the Torpantau Tunnel. Also known as the Devil’s Tunnel, Torpantau was 666 yards long and, at roughly 1,313 ft above sea level, the highest railway tunnel in the country.

Emerging from the darkness, the train began the long drop down to Brecon. Here Tommy and William left the train. As they were in no particular hurry, the father and son spent some time exploring the market town before setting out for the family farm at around 5:00 pm.

Cwm Llwch Farm

The walk to Cwm Llwch from Brecon is a stretch of just under 6 miles. After walking for about 3 hours, William and Tommy were just a quarter of a mile from the farm.

With their destination in sight, William chose to stop at The Login, a building used by soldiers training at the Cwm Gwdi rifle range as a campsite. That weekend it was occupied by soldiers from the South Wales Borderers. Their commander Major John Lloyd and his wife Alice were also at the camp.

Here William and Tommy met William senior and William John who had walked down from Cwm Llwch to meet them. While the men shared a drink with the soldiers, William John returned to Cwm Llwch on an errand. When Tommy asked to go with his older cousin the adults saw no reason to refuse; despite crossing two streams the path was largely across clear, open fields and much of it could be seen from The Login.

Halfway to the farmhouse, the sound of barking dogs startled Tommy. The little boy began to cry and decided that he wanted to go back to his father. William John, who used the track regularly, saw no reason to abandon his errand to accompany his young cousin so allowed him to return down the mountain alone while he carried on to the farmhouse.

This was the last time that Tommy was seen alive. However, a newspaper would later report that two people, one of whom was Alice Lloyd, had heard a boy calling for his father but were unable to trace the sound.

After completing his errand, William John returned to the camp. Barely 15 minutes had passed since he and Tommy had left.

The Search for Tommy

When his nephew returned alone, William quickly realised that his son was missing. With the help of the soldiers, they began to search the paths, trees, streams and undergrowth between The Login and Cwm Llwch. Many in the search party assumed that Tommy would be quickly found; he hadn’t been missing that long and couldn’t have strayed too far from the path.

However, the search proved fruitless. Despite the darkness that cloaked the valley, Lloyd’s men continued to search with torches until almost midnight.

When the search resumed at dawn the following day, word of the missing boy had spread through the valley and people from the nearby farms and hamlets turned up to help. Again the focus was on the lower sections of the valley.

Some of those involved in the search speculated that the little boy had become confused and taken a wrong turn on the path, climbing Pen Milan instead of descending towards The Login. There was even a suggestion that Llyn Cwm Llwch, the lake on top of Cwm Llwch, should be dredged but this, as well as suggestions that the top of the mountain should be searched, were quickly dismissed. No one thought it possible that the tired little five year old could climb to the top of the mountain. It seemed more likely that he had walked too far down the valley or fallen into a stream.

As the day progressed, and with Tommy still missing, William realised that he must inform his wife. Lucretia, had remained in Maerdy with their daughter. She was also 6 months pregnant and William didn’t want to cause her any undue worry.

Unable to leave Brecon and the mountain, William decided to send a telegram to Lucretia asking her to come to Brecon immediately because Tommy was ill.

On the Tuesday after Tommy disappeared, Lucretia arrived in Brecon to find William waiting at the station. A report in the Rhondda Leader explained that “on arriving at Brecon she was met by her husband, and whilst pursuing their way to the shepherd’s cottage the husband broke the news. The poor mother fell prostrate, bearing as she was a child of six months in her arms”.

Unable to join the search, there was little the grief stricken mother could do. On the 14th, Lucretia left Brecon for Maerdy. Instead of returning to the family home, she took her daughter to stay with her family in a house on Maerdy Road close to Capel Seion.

The story of the missing boy soon reached the national newspapers. The Daily Mail not only sent a reporter to Brecon to cover the case, they also offered a £20 reward for the recovery of the child “dead or alive”. While in Brecon the reporter worked hard on the case, helping to rule out the ‘gypsy abduction’ theory. Instead he forwarded the theory that Tommy had been abducted by a childless woman or couple. Other common theories included kidnap, murder and even that the boy was taken by an eagle.

The Tragic Discovery

After several weeks of searching William was forced to return home. He would return regularly to the area to continue the search. Heartbreakingly, William would later learn that he passed within yards of where Tommy lay. But the grass, which grows quickly during the summer months, had obscured the child’s body.

Almost a month would pass before the Hamer family would make the tragic discovery.

Abraham Hamer was a 29 year old under-gardener from Castle Madoc near Brecon. He was married to Esther and they had a number of young children including one who was 5 years old, the same age as little Tommy. Unsurprisingly, Tommy had been in the thoughts of both Abraham and Esther.

One night Esther had a dream in which she saw Tommy lying on a high ridge. The following morning she told her husband and suggested that they visit the area. To put his wife’s mind at rest, Abraham agreed.

On Sunday the 2nd of September the couple, along with some other family members, arrived at Cwrt-Gilbert, a farm near The Login on a horse and trap. From here they began the two mile walk to Cwm Llwch, passing the farmhouse and climbing Pen Milan. Despite the extensive search efforts, this location was rarely visited.

At around 2 o’clock that afternoon they found Tommy’s body lying face down in long grass, well away from the path. Heartbreakingly, he had died within sight of his grandfather’s home; Cwm Llwch was just half a mile below him.

The Hamer’s alerted the authorities and later that day Tommy’s body was carried from the mountain.

Tommy’s Return to Maerdy

The inquest into Tommy’s death was held at Cwm Llwch by coroner Dr W. R. Jones. The 8th of September edition from the Weekly Mail reported that the inquest concluded Tommy “died from exhaustion and exposure and that there was absolutely no evidence of foul play”. The inquest was unable to say how Tommy had reached that location.

Some speculated that Tommy had successfully returned to the army camp but, unable to find his family, started again for Cwm Llwch. This would explain the distressed cries Alice Lloyd and others heard. On his way back up the mountain, the little boy got confused and took the wrong path. Climbing higher and higher, he was unable to hear the shouts of the search party down below. As darkness fell, Tommy, by now hungry and tired, decided to lie down and go to sleep.

Following the inquest, Tommy’s body was taken by train to Maerdy. Here it was met by around 200 villagers. Led by Rev. Joseph Evans, a Welsh Baptist minister, and members of Capel Seion, they formed a solemn procession as the coffin was carried to the family home.

The following day, a Thursday, Maerdy stood still as the child’s coffin, covered with wreaths including one from Major Lloyd and the officers of Brecon, was carried from the family home to Ferndale cemetery.

The mile and a half route was lined with mourners; local schools closed for the day meaning schoolchildren stood alongside their parents, while many miners were also absent from work. The silence of the graveside was broken by Rev. Evans with the words “Wel, dyma Tommy bach yn y bedd” (“Well, here is little Tommy in his grave”).

In the months after Tommy’s death, Lucretia gave birth to a daughter. Sadly, the baby lived for only a few months.

The couple went on to have more children before Lucretia died in 1913. She was just 38. Her husband, William lived until 1958, dying at the age of 86.

For many years the family kept the sailor suit with collarette and light boots that Tommy was wearing as well as the whistle which hung on a string around his neck.

Many of those who had been involved in the search donated to Tommy’s memorial fund. Additionally, the inquest jurors donated their fees and Mr Hamer contributed part of his £20 reward.

George Hay, a local sculptor was commissioned to create a memorial obelisk which was placed near the spot where Tommy was found. Carved into the side of the obelisk is Tommy’s story whilst on the top are points of the compass, intended to help anyone else who may find themselves lost and alone on the mountain.

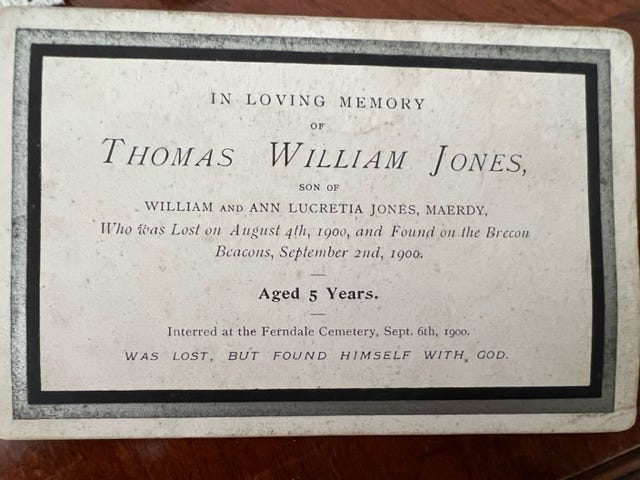

Meanwhile, closer to home, the family headstone in Ferndale cemetery reads:

‘O’r Bannau yn Brycheiniog,

Aeth Tommy bach i’r nef;

Aeth adref at yr Iesu,

Lle byth ni chollir ef.’

‘In the Beacons in Breconshire

Little Tommy went to heaven;

He went home to Jesus,

Where he will never be lost.'